How-to BBQ: Getting a bigger smoke ring

The smoke ring. A much sought after, magical thing in BBQ. The visibly identifiable symbol of good BBQ - even though it doesn’t indicate the quality of the BBQ (you can have great BBQ with no smoke ring, as well as terrible BBQ with a smoke ring) - it is a status symbol. There is an undeniable satisfaction cutting into your smoked meat and seeing the pink band around the surface of the meat.

This article is largely about an experiment - a lot of the science I learnt from a variety of other people and their writings, not least of all the folks at Amazing Ribs. My experiment in the pursuit of a big smoke ring is based entirely on the findings of their science experiments where they measured levels of certain gases in different heat sources. If you want to find out more about the background and science beyond what we cover here I highly recommend their myth-busting article on the topic here.

The Ultimate Guide to Epic Smoke Rings

1. Why do BBQ-ers obsess about the Smoke Ring?

The BBQ ring is not an indication of flavour, quality of the low-and-slow cook, or even a smokey taste. However, it is a common side-effect of cooking over fire, so it can largely be considered a fairly reliable indicator that meat has been properly smoked (and not just flavoured with smoke-enhanced flavour additives). Conversely, however, the absence of the smoke ring doesn’t tell us anything. It’s possible to smoke meat over live fire and achieve no smoke ring at all.

I suspect the reason we all love it is just tradition and history. When you first start BBQing the smoke ring is immediately noticeable, and different from all other kinds of cooking - which may allude to its popularity - the fact that in reality no other forms of cooking really results in a smoke ring.

When you smoke your first piece of meat and discover the smoke ring, its a satisfying feeling that doesn’t really diminish over further cooks. Being a part of a not-so-exclusive club of people who have discovered the delights of smokey, two-tone meat. From that first moment on, you will be chasing that little pink band every cook, experiencing the highs and lows that come with that quest as you go!

2. What is the Smoke Ring?

Ok, let’s get into the details.

Raw meat contains a protein called myoglobin. Myoglobin is responsible for storing and transporting oxygen to muscles, and depending on the oxygen level, is pink-to-reddish in colour (the more oxygen it is, the redder it gets, which is why supermarket packaged meats can sometimes look a bit grey - this is just lack of oxygen in the packaging). It is myoglobin that makes raw meat look pink-ish-red.

When myoglobin is subject to enough heat, it changes colour and becomes a grey-ish colour. This is the reason you have the varying colour on the inside of a steak depending on how well done it is. A rare steak should be a deep red colour where as a well-done steak will be grey. This is because as the myoglobin is cooked, the colour changes with heat. Whats more, this transformation is what is known as an irreversible reaction - which as you may have guessed, means it can’t be undone. Unfortunately there is no going back once you have over cooked your steak!

The pink smoke ring is formed because the myoglobin near the surface has not had its colour changed - which might sound counter intuitive given the outer layer is going to have been subjected to the most heat, and that usually its the inside that remains pink and the outer more grey on a steak, but this is to do with two other gases. Nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, specifically - these gases get absorbed by moisture in the meat and they have a reaction with the meat that essentially permanently sets the colour. Once nitric oxide or carbon monoxide hit the meat, they set the colour of the myoglobin to the initial, pinker state (at the start of the cook, the myoglobin is not yet cooked).

Obviously the gas doesn’t get a chance to penetrate very far into the meat before the colour changes through cooking, and hence, the smoke ring is formed.

3. How can I get a bigger smoke ring?

We have been through some of the details above, so maybe you have already come up with some tweaks that could be made to optimise your smoke ring, but there is one piece of all important information missing:

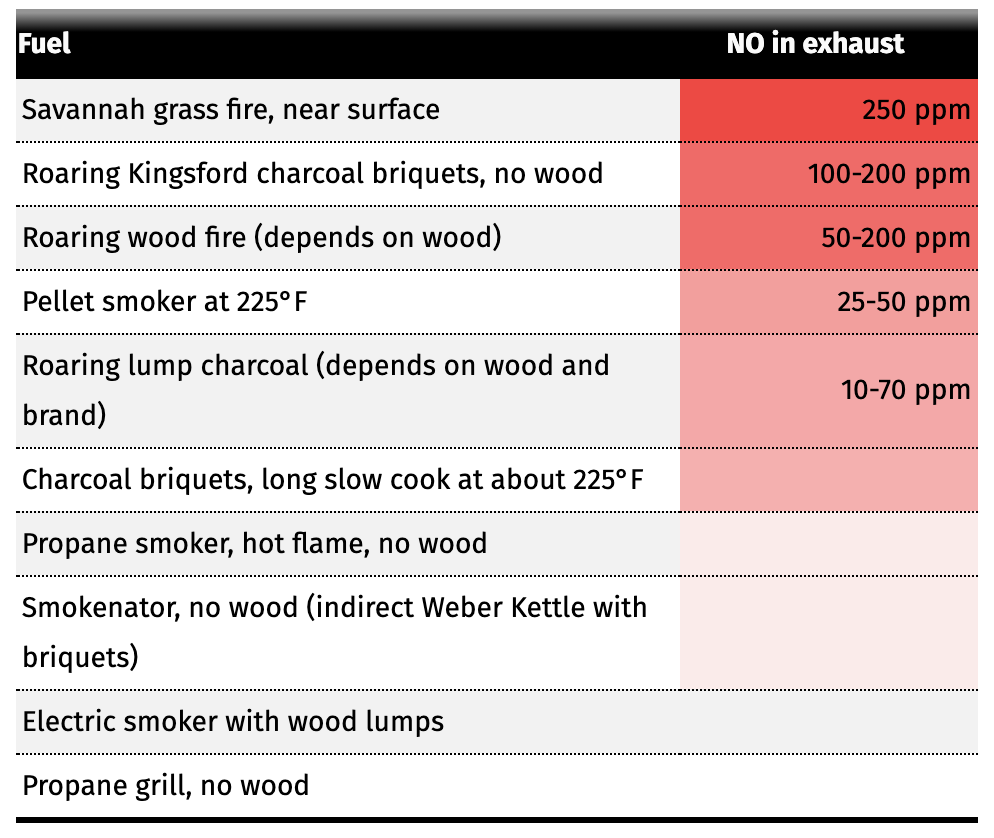

The above is from the AmazingRibs article all about smoke rings and this table was largely the basis for my experiment. The good news is, from the start, the numbers in the chart above (as well as generally interesting reading) do match up anecdotally with my experience:

Outside of a roaring fire, pellet grills have amongst the highest level of nitric oxide - Don’t let anyone tell you you can’t get smoke rings on pellet grills. I regularly see very impressive smoke rings on instagram and pretty much without fail when I read the description it was on a pellet grill such as a Traeger or the Weber SmokeFire.

Briquettes produce significantly more nitric oxide than lump charcoal - Another not entirely surprising one - lump charcoal is the most popular charcoal when cooking on kamado style BBQs, and a quick Google will tell you its not unusual for people to finish a cook and be amazed that their smoke ring has gone missing.

Roaring wood fires produce high levels of nitric oxide - check out the cooks from any offset smoker and you will know this is true.

It’s all good and well knowing the science, but can we actually use it to our advantage? What we know so far is the size of the smoke ring is based entirely on the depth that the nitric oxide or carbon monoxide penetrate into the meat before cooking transforms the colour of the meat.

Based on this, it seems like the options to maximise our smoke ring are:

- Increase the amount of nitric oxide the meat is subjected to

- Slow the time it takes for the meat to cook and stabilise the colour

4. The experiment: Maximising the smoke ring

With neither an offset or a pellet grill, both those options were out. And whilst I could have used wood in one of the other grills, I opted to use a more familiar setup so I could at least somewhat benchmark the outcome on my own experiences (obvious not at all scientifically, but having cooked many a cooks on my Weber Smokey Mountain I was confident that I’d be able to immediately tell if the smoke ring was better than average).

To maximise the result I was going to turn both dials at once.

4.1 Increasing nitric oxide

I obviously wasn’t looking to cook my meat on a grass fire, and having ruled out burning wood or pellets I was left with two choices:

- Roaring briquettes coming in at 100-200 ppm

- Roaring lump charcoal coming in at 10-70 ppm

Briquettes the clear winner here. Note that those two numbers were for roaring fires - low and slow cooking is never on a roaring fire, they are lower, smouldering fires to keep the temperatures down. Nitric oxide output for briquettes running low-and-slow isn’t even given a number on the chart (but is listed above the other things lower down) - so we can assume that the nitric oxide output correlates with the how hot they are burning, which suggests to maximise the output we want to get the coals burning as hot as possible whilst still maintaining low-and-slow cooking.

Reduce the amount of fuel

Normally, for a long low-and-slow cook I might use a chimney worth of hot briquettes that I would dump into the Weber Smokey Mountain on top of another pile of cold briquettes. With that amount of burning fuel, they would need to be smouldering fairly low, as the more burning fuel there is, the hotter it will be. With less fuel in there, we can have them burning hotter whilst still maintaining a lower cooking temperature.

For the experiment I reduced the starting briquettes to a little more than half a chimney full. This did mean that I had to top up the fuel a few times through the cook - but this experiment was not trying to take advantage of the Smokey Mountain’s qualities, but for our specific goal of a good smoke ring.

Maximise airflow

Oxygen is the key to a roaring fire - in normal operation, the Weber Smokey Mountain would not allow for a roaring fire as even with all the air vents open, there is still a limit on how much oxygen can get to the fire.

To get around this, I used a relatively well known mod that is usually used for when people want to cook hotter on their Smokey Mountain than the air vents allow, which essentially involves propping the door of the unit open. Ordinarily the mod works by simply increasing airflow beyond just having the vents open and allowing the charcoal to burn hotter - exactly what I wanted, but with a smaller amount of charcoal we could still keep the BBQ temperature easily at 110C/225F

4.2 Slow cooking time

Having taken steps to maximise the nitric oxide output, the next objective was to slow the speed at which the meat got cooked and the myoglobin transformed to the grey colour we wanted to avoid.

Start with cold meat

It might seem obvious, and this is a common trick on competition circuits, but starting with a colder piece of meat means it has a further temperature climb before that cooking process kicks in and changes our myoglobin colour. A short (30 minutes) in the freezer pre-cooking helps this (don’t cook from frozen though).

Check and spritz regularly

Spritzing meat during BBQ has two benefits here: 1) it provides more moisture that the nitric oxide can be absorbed into and 2) it helps cool the meat. Evaporative cooling (moisture on the surface of the meat evaporating and in the process cooling the meat) can help us here, by spritzing with cool liquid (water is fine) it both cools the meat on impact (as the heat energy in the meat is transferred to the cool liquid) and also then provides an evaporative cooling effect as that evaporates off.

Cook low and slow

Low-and-slow cooking covers a range of temperatures, traditionally around 110C/225F - 135C/275F - a fine range to be cooking at, but for the purpose of this experiment the lower the temp we cook at, the longer we will have for that smoke ring to form. Although we might get more nitric oxide produced if the fire is running hotter and the temps increase in that range, I didn’t find I needed to and the Smokey Mountain happily sat down at 110C/225F with the above adjustments.

5. Results & conclusion

Looking at the two photos below, the beef short ribs were cooked in the Smokey Mountain last Summer, with a pretty standard setup: cooking at 110C/225F, a chimney of hot coals to start, water pan filled, and honestly were probably among the best beef short ribs I have smoked to date. However, whilst there is a smoke ring, its fairly average and definitely not an impressive one (I was still happy with the smoke ring on cutting it).

The second photo, and the result of this experiment is a beef shin that I smoked last weekend. As you can see, a far more impressive smoke ring, and from my cooks on the Smokey Mountain and on the kamado, I can confidently say its the biggest ring I have achieved in many years of BBQ.

I will experiment again, in an effort to reverse this experiment and try to produce the smallest smoke ring. Another interesting observation, that you may have noticed, is that the hotter the day the lower your charcoal will be burning. On a hot summers day, you will likely have your fuel burning lower, where as on a cold winter day the fuel will have to burn hotter to counteract the energy loss to the harsher environment - so cooking in the winter should marginally improve your chances of a good smoke ring!

As always, happy to hear people’s experiences of smoke rings - good or bad!