The science of low-and-slow cooking

Smoking and BBQ is often low-and-slow cooking, that is, cooking for an extended period of time (anything from an hour through to double figures or overnight cooks) at a lower temperature. Normally in the range of 110-135C (225-275F). But why these temperatures and times? Most elements of cooking (from meat transformation to food safety) are a product of time and temperature, so why do we bother cooking low-and-slow? What’s so special about cooking at lower temperatures? Burning coal can, obviously, easily reach temperatures way above this range without any issue so it’s not an intrinsic limitation of grilling.

To understand this, we need to understand how meat is cooked and how the heat energy is transferred.

1. Basics of energy transfer: How is our food cooked

Before we get into any more details, we will take a look at how meat is cooked and how energy is transferred. For this example, we will think about a pork butt (pork shoulder - used for pulled pork) as its a large, roughly evenly shaped piece of meat.

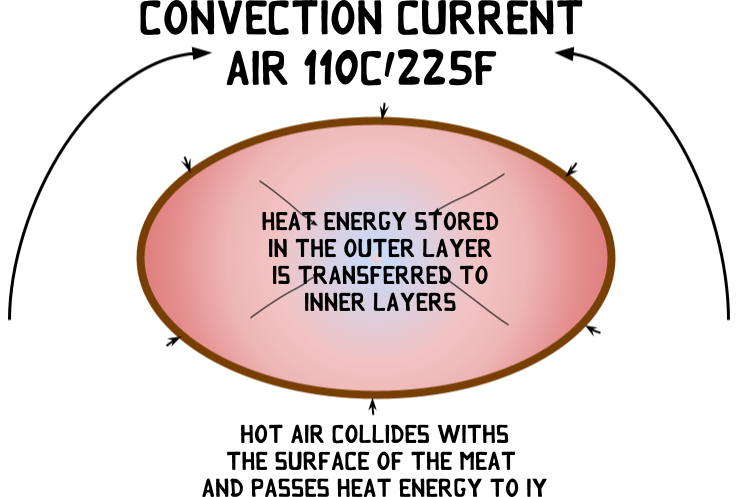

Ok, so we have our pork butt in the smoker, with the grill temperature sitting happily at 110C/225F, let’s take a look at whats going on:

So lets go through what is happening above:

- The air temperature is running at 110C/225F and an convection air current moving the hot air around our pork butt.

- The hot air in contact with the surface of the pork butt transfers heat energy to the outer part (the surface) of the pork butt - note, the air is only heating up the surface of the pork butt here

- the meat directly below the surface is basically being cooked by the surface of the meat - the heat energy stored in the surface of the meat passes on and that then cooks inner layers, and this continues to cook throughout

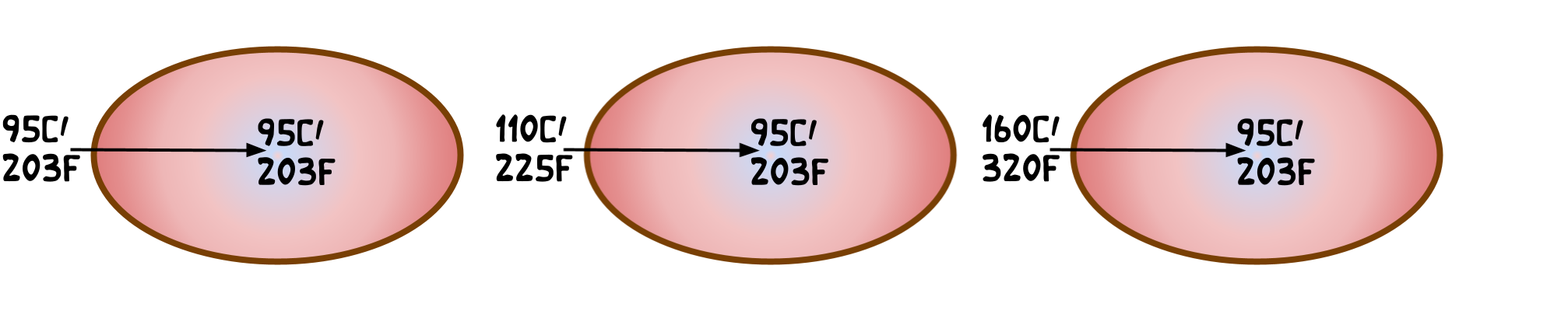

Point 3 is the important part here - the inner parts of the piece of meat are cooked by the outer part. It therefore means that for the centre of the piece of meat to be cooked to 95C, all the layers outside that need to also be at 95C. Whilst it is cooking, we get a gradient of temperatures, with the lowest temperature being the centre, thickest part of the meat and the highest temperature being the temperature in the grill.

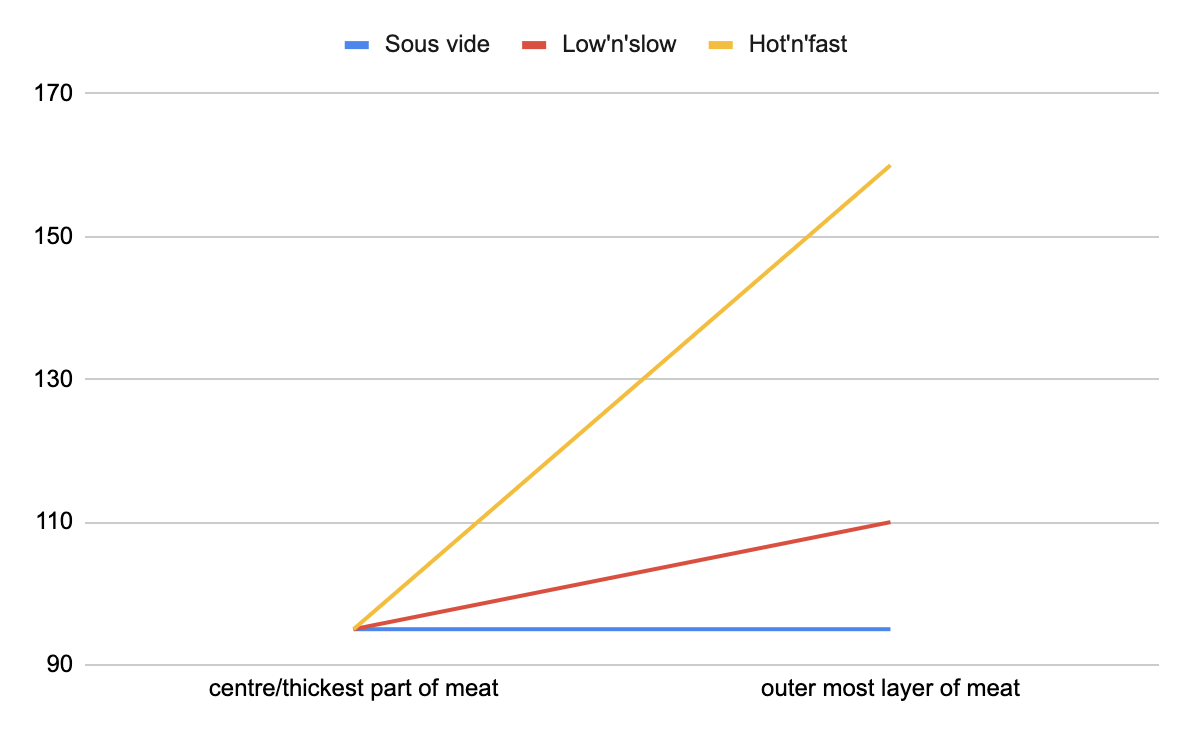

This temperature gradient is very important. This gradient is one of the main reasons why we bother cooking low-and-slow at all. If we illustrate this with some example scenarios (actual temperatures are not recorded numbers, but representative):

Sous vide is the ultimate low-and-slow form of cooking. Sous vide you cook the food in an environment where the temperature is controlled to be the exact same temperature as the target cook temperature. This has the effect of reducing our temperature gradient to a flat line - the centre of the food is the same temp as the rest of the food and as the heat source, there is no way for it to be over cooked.

Smoking style low-and-slow is based on the exact same principle, but a slightly higher temperature. This is traditionally cooking at 110C, with long cooking meats such as brisket or pork butt aiming for internal temperatures of around 95-98C, so the potential temperature gradient is not too steep (max 15C difference between centre and outer layer). I’m not sure why tradition settled on the 110 - 135C range - it could be any lower wasn’t that practical in terms of time to cook or possibly related to fire management (running a fire to low will leave it smouldering and not create ideal smoke for BBQ) or maybe someone discovered it and it just stuck.

Hot-and-fast, as you can see, results in the biggest gradient difference between the centre of the meat. The bigger the piece of meat, the greater this gradient will be.

2. So what does this mean in practice?

As you might have guessed, with some exceptions (a whole chicken for example), the goal is likely to be roughly even cooking throughout the meat with even temperatures. To have good levels of moisture and juiciness edge-to-edge, we want to flatten that gradient curve out as much as possible. If the centre has hit 95C we don’t want the outmost layer to be 150C plus.

So low-and-slow helps us achieve nice even cooking across large pieces of meat - and it doesn’t just apply to traditional slow-cooked BBQ cuts, this principle is also the reason we bother with the reverse-sear approach cooking steaks.

3. Are there any other benefits of cooking low-and-slow?

Yes! As well as even cooking, there are other reasons to cook cuts like pork butt and brisket low-and-slow, and that is because rendering of fat, and the breakdown of connective tissue (collagen) into gelatin (the magic process that makes BBQ work and extra moist and juicy) is not just a fixed temperature, its a combination of temperature and time. Well, actually its a combination of energy and time.

This is the second, really important point. Good BBQ isn’t just about edge-to-edge even temperature, its about juicy, moist gelatinous cuts of smokey meat. There is no hard and fast rule as to when collagen starts to break down into gelatin, but conventional wisdom (a.k.a smarter people than me who have run tests) suggests its about 60C/140F, and it the process speeds up as the temperature increases. However, when I say it speeds up, this isn’t to the point of being instantaneous at our target temperature of 95C. Even at that high temperature, for it all to break down and work its magic takes time.

The slower you cook it, the longer your pork butt, or brisket, will be sitting above 60C/140F, so the more time there is for it to breakdown.

Cook it hotter, and your internal temp will race through from 60C/140F through to 95C/203F a lot quicker, leaving less time for the magic to happen, so there is an increased chance that at the right internal temp, the meat won’t be tender and probing like you would want it to.

A common phrase you will hear is cook to feel, not to temperature - which is opposite to the messaging that you normally hear around BBQ about the importance of digital thermometers and temperature probes, but it holds true as you get towards the end of the cook.

Fun aside: the stall - the process where by cooking slows, sometimes to a complete halt, for hours on end is actually beneficial to the overall process. The stall essentially holds your meat at a lower temperature (but above the important 60C/140F) for sometimes as much as hours, which will help with the breakdown of collagen. It’s almost as though nature & science wants us to eat delicious BBQ!

4. Conclusion

Low-and-slow is the reason that BBQ works so well, it is the magic that transforms tough (often cheaper), hard working cuts of meat into beautifully tender, soft and moist meat. It’s worth taking your time on the cook and enjoying it.

That said, despite the science, if you have a method that works well for you, and you run it hotter, then keep at it! BBQ is also a lot about knowing your kit, meat and environment and once you get some decent cooks under your belt you will get a good feel for it and just keep doing what works well for you!

As always happy to have questions or suggestions!

Heading image, a photo of a BBQ thermometer, by Timo Müller